James Barth’s approach to self-portraiture is as complex and multifaceted as the artist herself, exploring self-representation in a post-internet era where accessibility can quickly lead to vulnerability. Using a combination of analogue and digital techniques, Barth has carved out a practice that is totally unique and eerily familiar.

Your practice is most obviously situated in self-portraiture, but are there other aspects you consider integral?

Sometimes it feels impossible to talk about my paintings without referring to self-portraiture, but they can also be viewed through the lens of post-medium and post-analogue painting. There’s so many intersections within each work, whether it’s the medium and the way it’s used, or how the production of each work contemplates on time and its relationship to self-portraiture, and how self-portraiture in turn relates to my experience as a trans person. It’s a multilayered stack of things that don’t necessarily connect but are all holistically part of my work. Sometimes I struggle to encapsulate my practice, but maybe the point is that it is messy to explain. The explanation is already embodied in the work, and often I feel like the work outpaces the language I have available to describe it.

Your process is distinctive, combining screen-printing and brushwork. How did this come about?

Originally it began as a way of speeding up the process of getting the paintings started, but I ended up really loving the results and saw a lot of potential there. I was reading a lot about the post-medium condition, on painting’s ability to score time, and looking at conceptual painters like Louisa Gagliardi who combines digital print technologies with experimental media to replicate painterly marks. And I was reflecting on being taught that mark-making and gesture, and the labour of painting, were all important. I wanted to challenge that thinking. So I experimented with using an oil medium but reducing the mark making to one giant screen swipe and a series of brushstrokes back and forth to obscure the screen-printing process, while also alluding to art-historically important works like Gerhard Richter’s use of the blur.

Richter once described grey as “the ideal colour for indifference” when discussing its ability to remove sentimentality from an image. I’m wondering how influential he is on your practice, and if you employ your monochromatic palate for similar reasons?

I was very inspired by Richter. I like that idea of connecting to the photographic through the proxy of painting. I guess my approach to the grey palate is similar too. I definitely use it as a way of making representations of myself less accessible. There’s an austerity to the way I represent myself which I think holds a lot of power. The mechanism of screen-printing also allows an indifference that is very explicit.

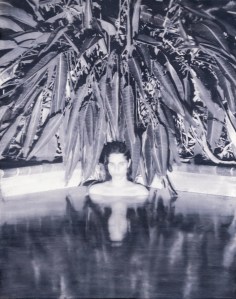

You’ve referred to Self Portrait in Pool 2018 as a transitional work in your practice. Can you explain why?

I love that painting, but it was created at such an explicitly transitional stage for me – both in terms of when the photo was taken, and how the work was made. It was one of the first examples of the print paintings.

Your 2019 show Screen Tests at Milani Gallery, Brisbane, featured self-portraits taken from digital avatars of yourself rather than photos – I’m thinking of Umbrageous Self-Portrait and Multi Portrait (life modelling). Was this another way of maintaining that inaccessibility?

My avatar selves are like actors that allow me to represent myself without explicitly showing myself – the works become an idealised version of me. They’re more about expression than actual representation, because I don’t think my self-portraits can possibly epitomize me. They’re way too still. I’m fidgety!

Screen Tests also featured still lifes such as Computers, Cables and Shadows 2019. Were they device for obscuring the “self” in your work?

To a degree, yes. But they also act like small conversations within a body of work which, viewed in conjunction with the self-portraits, provide more perspectives on me. They fill in details that an image of myself can’t. I think they also let me position myself as an observer of my life and surroundings occasionally, and not cast solely as the “observed” subject.

How important is trans representation in your work?

It’s important, but only to the extent that I am representing myself and my own experience. I make works from my own need for visibility, but I’m conflicted by it. I’m conservative with how I show myself and only give people access in very specific ways. People outside the trans community often consider visibility the main priority, but visibility can also create complications and risks for trans people. I’m aware my work speaks to other people’s expectations of me, especially strangers. I want to provoke discussions on that, but I try to do it in a way that is subtle.

Last year you also collaborated with Spencer Harvie on the animated short ZONWEE: The last known recording of a daydream, which was presented at Boxcopy, Brisbane. Is it something you’d like to revisit?

Definitely. It was a logical progression for me because I wanted to experiment with motion and expression. My paintings are so still; they’re so focused on stillness it’s almost a subject in itself. And it helped to have an amazing artist like Spencer to collaborate with, because it was a huge learning curve going from still to moving images.

Your practice has been through such an evolution over the last few years. What’s next?

My work is quite romantic but it’s also a very clinical way of looking at self. I’m trying to be more playful and expressive – to find a way to step outside my self-imposed austerity while still retaining some sense of remoteness.

First published in Vault Magazine, Issue 32, 2020